[ Grumble ]

3. The Interpretation

3. The Interpretation

Not Really Really (17-SS-4) can be seen as describing a scene that has been covered by a gossamer curtain. It acts like a landscape that fades or withdraws behind a curtain. Viewers can barely see what is behind it and only get a glimpse if they take the initiative to draw back the curtain.

The term ‘curtain’ brings to mind Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ work Untitled (Loverboy) (1989) which is pictured above.[1]Untitled (Loverboy) is difficult to recognize as an artwork in a gallery space, even though it has been announced as an artwork on the label and through the context of the white cube. After reading the text it still needs the viewer to sense the meaning behind the artwork. In the work, Gonzalez-Torres digests his life experiences and ruminates on using materials to speak about these experiences. At the same time, he does not overinterpret the works so that they relay this exact same experience but provides viewers with an evocative set of materials that they can interpret into their own life experiences.

I am amazed by the way that the fabric Gonzalez-Torres uses has far exceeded the way in which a curtain usually appears. Gonzalez-Torres’ curtain becomes not just a curtain anymore, it changes according to the different experiences that it provokes in each viewer. The curtain becomes not just an object but also taps into the viewer’s memories. For example, when the fabric quivers in the wind this could evoke subject-specific interpretations. A curtain is not just simply a curtain.

Correlating with the above approach, if I tried to describe the scene behind Not Really Really (17-SS-4) it would become a contradictory or paradoxical situation because it would reinsert a dominant authorship and not leave the work open to audience interpretations. In contrast to the former approach, I attempt to overlay the mystery of the blurred scene even further. For me, this is more attractive than uncovering the curtain to explicitly describe the scene of the refreshed egg yolk to an audience. Imagine that the experience is similar to the way in which audiences interrogate a painting; different interpretations occur if the painting is observed from far away or whether the viewer engages with it up close and focuses on its details. The closer the viewer looks at the egg yolk, the more blurred it will become because their interpretation may evolve not to be just about the egg yolk but their self-experience in relation to the effects evoked by the egg yolk. From a distance, the viewer may not interpret the egg yolk to be an artwork and could dismiss it on this premise.

There is a similarity between Jospeh Kosuth’s, One and Three Chairs (1965), and Michael Craig-Martin’s, An Oak Tree(1973), as both works are not just discussing the object (artwork) itself but wondering about the effects a thing may have if it exceeds or goes beyond the artist’s/viewer’s expectations. Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs has loosened the object’s relationship to the human(s) subject. Kosuth separated one object into three layers; a real chair, a photograph of a chair and a name/definition of a chair. By juxtaposing these three different approaches to the object (chair), Kosuth took apart the object and its definition.

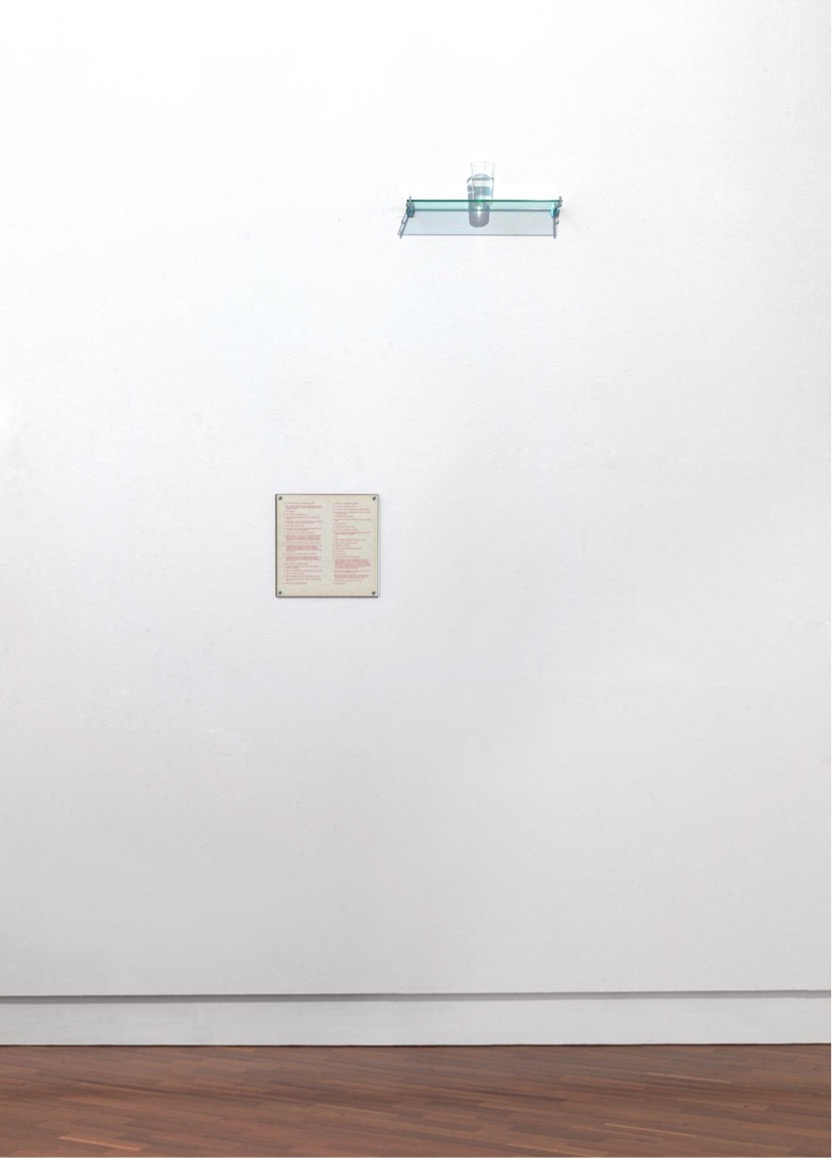

Furthermore, in the work of An Oak Tree, a glass of water is undoubtedly categorized as a tree by the artist. The uncanny label below the artwork troubles the viewer’s familiarity with a glass of water and encourages them to imagine that the glass of water is an oak tree. As a result, Craig-Martin suggests that we should question the methods and stability in naming objects. On the other hand, as anobject the tree is extremely familiar to most viewers, which will cause the viewer to see another object inside the institutional label. However, the gaps, produced between name and object, are too deep and broad for the viewer to see one thing in the place of the other. Craig-Martin’s claim (label) and image (tree), produces an obvious crack between name and thing. This breach subverts the stable identification of a glass of water and in its place creates an unlimited potential definition of what a glass of water could be for the viewer. In contrast, anthropocentric thinking frames objects and limits them through identification, definition, and allocated purpose.

Humans are too familiar in following this framework that chains objects to their identification and function. It is a reductionist approach for expediency (immediate recall or smooth running) but there is not necessarily just one effect or reading that can be generated by things. There could be several ways of identification and function, which can be produced through the thing itself and in relation to a different reader, viewer, or user.

![]() Michael Craig-Martin, An Oak Tree, 1973

Michael Craig-Martin, An Oak Tree, 1973

Ready-made objects can be found everywhere in our human ordinary lives. When a viewer encounters a ready-made object in a gallery it is framed as an artwork due to its surroundings (institutional context: gallery, exhibition, artist’s signature, installation, literature etc.) and this disconnects it from its everyday meaning or interpretation. In a sense, it provides a spotlight for the object and our usual assumptions in relation to it. It can also provoke confusion in the viewer, who may struggle to identify the familiar ordinary ready-made object in front of them depending on how it is framed or put to use. This enables the artists, institutions, and viewers to challenge their habitual encounters and the way in which they deploy objects. For example, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), is both an actual vitrine and symbol of a fountain. Duchamp famously tested the boundaries of the art institution by attempting to introduce a readymade latrine complete with a fictional artist’s signature into an exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists at The Grand Central Palace in New York, 1917.[2] Through this he questioned the parameters of what makes an object an artwork. Duchamp deployed the Fountain to reflect on the institutional strategies that validate and frame objects as artworks; the artist’s signature, it’s staging (on a plinth), the inclusion in an exhibition, as well as press and literature. He held the object up to examination so that viewers could critically look at the society which configures and authorises objects. Fountain (1917) also challenged the symbolic meaning of the toilet and undertook the conceptual challenge of placing a readymade in a gallery, in order to enable the viewer to question their habitual reading of the object and to provoke their imagination.

Michael Craig-Martin, An Oak Tree, 1973

Michael Craig-Martin Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917)

Both artists, Joseph Kosuth and Michael Craig-Martin emphasize this block while, simultaneously, playing with the language and identity of an object. The awkward friction between language and object is similar to describing the view outside of a window which has a curtain in front of it. The scene is present but absent as well, it exceeds itself through what is imagined by the viewing subject and its openness to projection and interpretation.

In the above scenario, the artwork becomes not only relational with the artist’s interpretations but also that of the various audience interpretations. An object becomes not just an object when the evocative material encourages the viewer to hover around the artwork with their own thoughts. These thoughts connect with the viewer’s own life experiences and emotions, which are provoked by the effects of the artwork toward the viewer themselves. This again relates to Roland Barthes’ concept in Death of the Author (1967), in which the interpretation (often produced in written form - title or description - to supplement the artwork) should not narrow down meaning but open itself up to interpretation. Barthes declared that ‘… each of us has their own rhythm of suffering’,[3] there is no standard and the weight of suffering is dependent on the individual as well as the gravity of external effects. Every work is rewritten again, every time when being viewed.

[1] Felix Gonzalez-Torres (1957-1996, Cuban) was an American visual artist. Gonzalez-Torres was known for his minimal installations and sculptures in which he used prosaic materials such as candy, sheets of paper, light bulbs and wall clocks. Gonzalez-Torres’ exemplary importance in providing a subtle and often intentionally cryptic language of queerness, one that foregrounds romanticism, and recasts the language of minimalism and conceptualism as vehicles for affective content, is one of his most important contributions to the canon.

[2] Fountain (1917) was rejected by the committee, which went against the Society’s own rules that stated all works would be accepted by artists who paid a fee to be exhibited, but the work was never placed in the show area. Marcel Duchamp withdrew from his position on the panel organising the exhibition as he did not agree with this decision.

[3] Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary (London: Notting Hill Editions, 2011), 19.

[2] Fountain (1917) was rejected by the committee, which went against the Society’s own rules that stated all works would be accepted by artists who paid a fee to be exhibited, but the work was never placed in the show area. Marcel Duchamp withdrew from his position on the panel organising the exhibition as he did not agree with this decision.

[3] Roland Barthes, Mourning Diary (London: Notting Hill Editions, 2011), 19.